Seattle physician’s social post highlights shift in hiv care over three decades

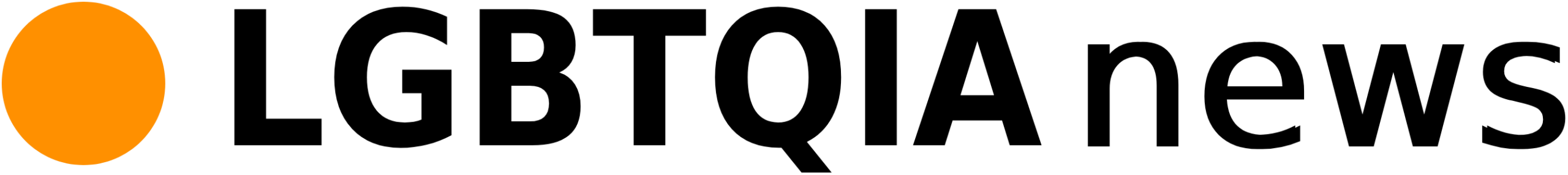

A Seattle-based physician, Peter, contrasted two clinic scenes in a social media post that drew widespread attention. He placed a bleak ward visit in February 1996 beside a celebratory clinic visit in February 2026. One image showed a young hospice patient barely able to swallow. The later image showed the same man married and thriving. The two snapshots illustrated dramatic changes in hiv care.

The post prompted hundreds of responses recalling fear from the 1980s and 1990s and gratitude for life-saving treatments. The thread shifted the focus from individual survival to broader issues. Commenters raised questions about funding, research support and persistent health disparities. The exchange underlines that medical advances alone have not resolved systemic barriers to care.

From hospice to honeymoon: a personal story of medical progress

The exchange underlines that medical advances alone have not resolved systemic barriers to care. In a social post, the Seattle physician Peter recalled an encounter from February 1996 at an AIDS long-term care facility.

A young man in his twenties lay severely wasted. He received total parenteral nutrition (TPN) because of cytomegalovirus (CMV) esophagitis and could not swallow. He was on a morphine pump for severe pain. Staff and clinicians expected that he could not tolerate oral medication.

The patient asked nonetheless about newly available HIV medicines. He insisted on trying. He managed to take pills daily and, over time, improved enough to leave hospice.

The episode illustrates a clinical turning point: antiretroviral therapy that was then emerging could rapidly change an individual prognosis. It also highlights persistent gaps in access, adherence support, and broader social care that affect outcomes despite therapeutic progress.

In February 2026, a Seattle physician described a striking clinical encounter. He saw a middle-aged, well-dressed patient who showed wedding photos and discussed plans for a honeymoon in the South Pacific. The patient had marked 25 years at a technology company and had built a life that would have been unimaginable three decades earlier. The physician, Peter, said: “This is why I do what I do.” The encounter illustrates how the arrival and widespread adoption of effective antiretroviral therapy transformed prognosis and daily possibilities for people living with HIV.

Collective memories: grief, compassion, and stigma

The medical progress that enabled that clinical scene did not erase the epidemic’s collective memories. Clinicians, families and communities still recall high early mortality, overwhelmed hospices and the long arc of activism that pressured governments and companies to act. Those memories shape professional practice and patient expectations today.

Stigma endures as a structural barrier to care. Social discrimination, inadequate insurance coverage and localised shortages of specialised services continue to deter testing and treatment in many communities. Gaps in adherence support and integrated social services also limit gains from modern therapy.

The contrast between personal recovery stories and ongoing systemic failures highlights a persistent policy challenge. Scientific advances have improved individual outcomes. Yet equitable access, sustained support and broader social care remain necessary to translate those advances into population-level health gains.

Yet equitable access, sustained support and broader social care remain necessary to translate those advances into population-level health gains. The original post drew hundreds of replies from people who lived through the pre-antiretroviral therapy era and from clinicians who cared for them.

One correspondent said they lost an uncle to AIDS in 1997 and called the transition from a perceived death sentence to a manageable illness among life’s greatest comforts. A registered nurse who worked in an emergency department in the 1980s described pervasive uncertainty about contagion and routine decisions such as whether to reuse a thermometer. She recalled the extreme isolation many patients endured and the rare, meaningful human contact—one patient later told his doctor that a nurse’s touch had been his first voluntary contact in more than a year.

The responses underscore gaps that medical advances alone do not close: social support, clear infection-control guidance, and funding for long-term care remain essential to prevent past harms from repeating. The thread received hundreds of replies detailing similar memories and concerns.

The thread received hundreds of replies detailing similar memories and concerns. Not all recollections were of survival. Several respondents described partners and friends who died in the mid-1990s, with some saying those losses occurred just before effective treatments became widely available. “We just barely missed the window,” one commenter wrote, recalling a spouse who died in the spring of 1996. These accounts underscore the timing of medical advances and the narrow margins that determined life or death for many.

The human need for touch and dignity

Many replies emphasized the importance of basic human contact and the cruelty of stigma. Respondents reported that, beyond medications, patients needed compassion, sustained community support and the removal of discriminatory behaviors. Stigma not only limited access to services but also deprived people of physical comfort and any sense of normalcy, deepening the social wounds left by the epidemic.

Those personal narratives highlight how social responses amplified medical harms. They also point to areas where non-clinical interventions—peer support, anti-discrimination efforts and community-based care—could have mitigated suffering alongside treatments.

Progress meets policy: victories, cuts, and persistent disparities

The next section examines how policy choices shaped access to life-saving therapies and why disparities persist despite scientific progress.

Policy choices, access and persistent disparities

The historical advance of treatment did not erase structural barriers to care. Public policies shaped who could reach life-saving therapies and how quickly services expanded. Funding decisions, eligibility rules and local implementation determined access in many communities.

Recent national surveillance data highlight continuing inequities: infections and outcomes remain concentrated in Black and Hispanic communities. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported 4,496 HIV-related deaths among people aged 13 and older in the United States in 2026, underscoring that the epidemic endures despite therapeutic progress. The next section examines how specific policy choices affected access and why disparities persist.

The federal government set a goal in 2019 to end HIV transmission in the United States by 2030. Current trends show the decline in new infections is not rapid enough to meet that target. Proposed reductions in federal health budgets and reports of canceled research grants have raised concerns that hard-won momentum could stall or reverse. Those policy shifts threaten the continuity of services that underpin prevention and early treatment.

Implications for communities and public health

Reduced funding would directly affect core public-health activities. Routine testing, contact tracing, syringe services and public education campaigns depend on steady support. Interruptions in these programs can delay diagnoses and increase the risk of onward transmission.

Marginalized groups are likely to bear the greatest burden. Communities already facing barriers to care — including limited access to clinicians, transportation and culturally competent services — could see deeper disparities in outcomes. Public clinics and community-based organizations that provide low-cost or no-cost services would face capacity shortfalls if grants and contracts are cut.

Research disruptions also carry practical consequences. Cancelled or delayed studies slow the development and deployment of new prevention tools and treatment strategies. They can limit evidence needed to target interventions effectively and to measure progress toward public-health goals.

Maintaining steady investment in prevention, treatment and research is central to reversing current trends. Policymakers and program managers will need to prioritize continuity of services to protect recent gains and to reduce inequities in care.

Funding cuts could reverse progress for the most vulnerable

Public health experts warn that reductions in funding for prevention, surveillance and research would disproportionately harm the most vulnerable communities. They say sustained investment is required to protect recent gains in treatment and prevention. Without it, progress may be undermined and disparities could widen.

Peter’s story functions as both tribute and caution. From a hospice room in February 1996 to a wedding slideshow in February 2026, the narrative illustrates how medical advances transformed individual destinies. It also highlights that those advances depend on ongoing commitment to equitable care, continued funding, and efforts to dismantle stigma that once denied people touch, dignity and hope.

Policymakers and program managers must prioritize continuity of services, expand access to care and maintain robust prevention and research programs. Targeted funding, durable surveillance systems and anti-stigma initiatives are central to sustaining declines in transmission and reducing inequities in health outcomes.

Stories such as Peter’s underscore what is at stake: scientific success must be matched by sustained policy choices and community support to ensure gains endure.